#Trinity60

Fraser Macdonald

"Plan the dive, dive the plan." For over 50 years, this mantra guided hundreds of Trinity students from the safety of the school pool to the depths of the Red Sea and beyond.

The story of Sub-Aqua at Trinity: from glueing wetsuits to whale sharks

By Fraser Macdonald (Class of 1963, Head of Spanish, 1971–2008 & Founder of TSAC)

The origins of the Trinity Sub-Aqua Club (TSAC) lie in a moment of classroom frustration. In 1971, I joined Trinity as a new teacher. Like all staff then, I was expected to run an extracurricular activity. There were no vacancies in swimming, so I was assigned to command the Royal Naval Section of the CCF.

For three years, I taught chart work, navigation, and knots in a classroom. It became increasingly dispiriting work—teaching the theory of the sea without ever getting wet. To the cadets, it felt like just an extension of the school day.

The spark that changed everything came out of the blue in 1974. I received a phone call from Peter Coy at Alleyn's School, asking to borrow some equipment for their inspection. When he came over, I showed him our facilities, specifically the pool which is three metres deep at the far end.

We got chatting about the difficulty of maintaining cadet interest. He looked at the pool and said: "Why not teach them Sub-Aqua diving? Everything in the Naval syllabus fits—tides, weather, ropes, chart work for finding wrecks. And you have the practical facility right here."

I admitted I had never dived in my life. Peter, who happened to be a British Sub-Aqua Club (BSAC) Advanced Instructor, made an offer that would define the next three decades of my career: "I will come over every Monday evening and train you and a pioneer group of three boys."

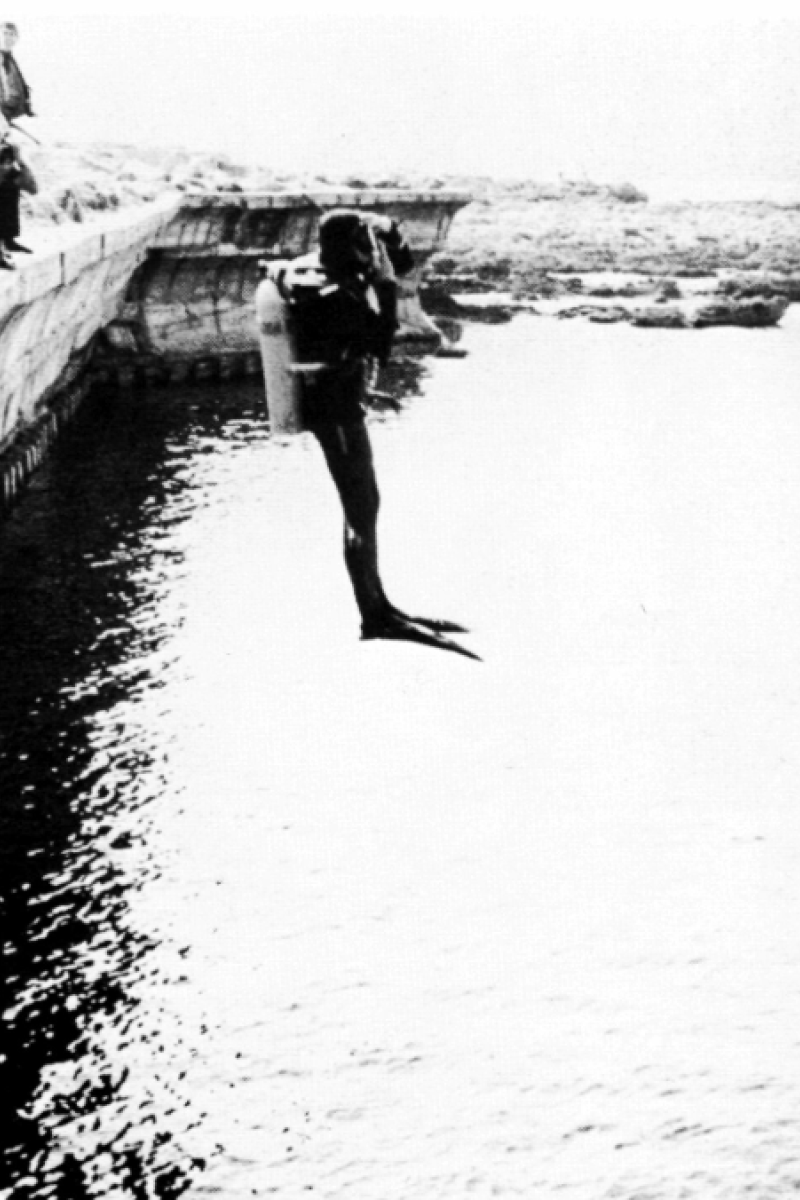

Peter was as good as his word. For a year, he trained our small pioneer group every Monday night. The regime was rigorous, based on the BSAC maxim: safety first.

In those early days, we had almost no budget. We started with just four cylinders.

-

The DIY wetsuits: We couldn't afford to buy suits, so we made them. We bought sheets of neoprene, marked them out with templates, cut them, and glued them together ourselves on the pool side.

-

The "Mae Wests": Modern buoyancy compensators (BCDs) didn't exist. We used surface life jackets, exactly like the ones you see in an aircraft safety demo. They were useless underwater—you had to control your buoyancy entirely by lung volume.

We learned to clear masks, share air ("two breaths, two breaths"), and navigate underwater using the ripples in the sand (which always run parallel to the shore). By 1975, we were ready. We registered as an official branch of the BSAC and headed to the coast.

Our first expeditions were thrilling—camps in Cornwall at Porthkerris, diving in Swanage and Lulworth Cove. By 1976, the Headmaster had noticed the enthusiasm. He asked if I would open the club to non-CCF students. I agreed, on the condition that we received proper funding. That decision transformed us from a small cadet unit into a school-wide institution.

With funding came equipment and ambition. We started running major expeditions, utilising military bases thanks to our CCF connection. We dived from HMS Daedalus in Portland and Britannia Royal Naval College in Dartmouth.

Soon, we looked further afield.

-

Cyprus: We based ourselves at RAF Akrotiri. I discovered a transport depot nearby and managed to borrow a 4-tonne lorry. We stuffed it with diving kit and students and drove around the entire island, shore diving every day.

-

Malta & Gozo: We visited the islands at least 12 times. A highlight was always Comino, where students swam through the cave system which appears in a James Bond film.

-

The Red Sea: We took students to Aqaba (Jordan) and Hurghada (Egypt), diving the legendary SS Thistlegorm wreck—a cargo ship from WWII full of motorbikes, trucks, and munitions.

Perhaps the most extraordinary chapter in the club's history involved the RAF. In the mid-80s, I qualified as a Joint Services Sub-Aqua Diving Supervisor—the only civilian on a course of regulars at Fort Bovisand. This qualification allowed me to take cadets diving on military exercises.

It also put my name on a Ministry of Defence computer. Twice, I was called up and flown 8.5 hours on an RAF Hercules transport plane to Ascension Island in the middle of the South Atlantic to train RAF divers stationed there.

On one trip, I was diving under the hull of a massive Maersk tanker anchored offshore to check the hull. I looked down, 50 metres below, and saw hammerhead sharks feeding. Then, a shadow covered us.

It was a whale shark—the biggest fish in the sea. It was the length of the tanker itself, over 40 feet long. It swam silently past us, its tail fin towering over us. It was a filter feeder, harmless, but the sheer scale of it was a shock I will never forget.

A professional legacy

By the time I retired in 2008, the club had come a long way from four cylinders and home-glued wetsuits. I left behind a fully operational diving school with:

-

15 full sets of modern cylinders, regulators, and BCDs.

-

A large compressor system for instant air fills.

-

A purpose-built RIB (Rigid Inflatable Boat) equipped with GPS, echo sounders, and a magnetometer for finding wrecks.

But the real legacy is the students. Many Sixth Formers qualified as BSAC Instructors before they even left school. As I used to tell them, walking into a university scuba club as a qualified instructor at age 18 is "gold dust". It showed leadership, technical skill, and responsibility—the very things education is supposed to provide.

Based on a talk given by Fraser Macdonald to the Trinity Sub-Aqua Club 26th November 2025

Full transcript here.